Ramsey County History Magazine

Spring 2010, Volume 45 # 1

For these and other local history resources, please check out my friends at Ramsey County Historical Society.

John Cotton, left, was an outstanding athlete and second baseman for the Twin City Gophers, his Marshall Senior High School team, and other professional teams in the 1940s and ’50s. He and Lloyd “Dulov” Hogan, right, and the other unidentified player in this photo were part of the thriving black baseball scene in Minnesota in the middle of the twentieth century. Photo courtesy of the Cotton family. Photo restoration by Lori Gleason.

Imagine you woke up one morning, ate breakfast or had your cup of coffee, showered, dressed and went to work. Upon arrival you were told to enter through the back door! Or because you had blue eyes, you couldn’t work there anymore.

Most of us couldn’t even imagine that set of circumstances. I can.

Prior to enrolling as a student at the University of Minnesota in the fall of 1968, I was fresh out of the U.S. Air Force and I needed a job to make some money to attend school. So I made contact with Charles Simmer, the former principal of my St. Paul high school, Mechanic Arts. He suggested that I seek an internship with the electronic contractors union. I accepted the internship because I could make some money for the summer, but my real goal was going to the U of M to pursue what I wanted to be, not what “Us Negro people should be”—skilled with their hands; not with their minds.

I was given an assignment to work as an apprentice electrician at a work site on St. Anthony and Virginia streets. I walked to the site and was greeted by the supervisor, whose first comment was, “Phew, we thought they were going to send one of those ‘niggers’ down here.”

Not long before my encounter with this supervisor, members of the Rondo community had challenged the changes going on. They wanted to make sure all the promises of jobs that would be brought on by the construction of the section of Interstate 94 that was about to rip through St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood would be met. There had already been many complaints that African Americans could not even get general labor positions in the construction trades because the black applicants for these jobs lacked the “skilled labor experience” that other applicants supposedly had.

My comment to this man was, “Who do you think I am?” For sure, I wasn’t a Nigger. But my father was African American. Of course when the site supervisor took a look at my features, he had mistaken my heritage. Perhaps he thought I was Mexican (my mother was Mexican) or Native American. Whatever the reason, he began to stutter and stammer but never really gave an answer. I left for lunch that day and never went back. It was clear I wasn’t even welcome to be an apprentice electrician at this workplace, which was only a half block from one of my childhood homes.

Here in Minnesota and the Twin Cities, denial and Jim Crow was a reality.

Untold Story

The exhibit that Ramsey County Historical Society has mounted is a tribute to everyday people who were also special athletes. They are some of the great baseball players who struggled to overcome racial indignities and the lack of recognition for their accomplishments that resulted from the color of their skin. Their absence from baseball history until recently is communicated throughout the exhibit in their own words and in the words of those who knew them. Their participation was denied due to racism; not their ability to play. What they experienced while playing baseball is a reflection of the troubled history of race relations in the United States.

Setting the Stage: Separate but Not Equal

Following the end of the Civil War, the Congress passed three amendments to the U.S. Constitution that established conditions under which the defeated states of the Confederacy could be readmitted to the Union. The Thirteenth Amendment (1865) outlawed slavery; however it did not provide for equal rights or citizenship. The Fourteenth Amendment (1868) granted African Americans citizenship. The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, stated that race, color, or previous condition of servitude could not be used to deprive a man of the right to vote.

Against this background of constitutional legislation, all-black baseball teams had been playing each other since 1860, mainly in East Coast and Middle Atlantic states. Despite racial prejudice following the Civil War, African Americans had also played on minor and major league teams until about 1890. On July 14, 1887, Cap Anson’s Chicago White Stockings refused, however, to play the Newark Giants of the International League because the Giants roster included two African American ballplayers, Fleet Walker and George Stovey. The Newark team benched Walker and Stovey, but later that same day, the owners of International League teams voted to refuse future contracts to African Americans, citing the “hazards” imposed by such athletes. The owners of teams in the American Association and National League quickly acknowledged this precedent with their own “gentlemen’s agreement” not to sign black baseball players.

By agreeing to withhold baseball contracts to black baseball players, the owners indirectly modeled the racial attitudes that the U.S. Supreme Court subsequently upheld in Plessey v. Ferguson (1896), a case dealing with segregated railroad facilities. This legal precedent held that as long as “separate but equal” rail accommodations existed, then racial segregation did not constitute discrimination. In practice, however, many states, particularly in the South, took Plessey v. Ferguson as a blanket approval for enacting restrictive laws, generally known as Jim Crow laws, which gave African Americans second-class status.

Although some Minnesotans believe that Jim Crow laws existed only in the states of the former Confederacy, many of these same restrictions were alive and well in our state in the twentieth century. Minnesota may not have had separate water fountains or separate restrooms or separate schools for African Americans and whites, but says Harry “Butch” Davis Jr. of Minneapolis, “Blacks knew their place; you couldn’t get a mortgage outside a certain neighborhood.” Jim Robinson of St. Paul, tells how “African Americans couldn’t eat in white, firstclass restaurants; they were restricted to sitting in the balcony at movie theaters, and were only allowed to stay in certain hotels in the Twin Cities area.”

While I visited with a gentleman at the opening of the baseball exhibit, he shared with me this story: “When I purchased my home in south Minneapolis, I wanted to find out the history of my home and researched the deed.” What he found out was that the original deed included a statement that “this property cannot be sold to niggers or Jews.” “I was appalled,” he emphasized. To me, this anecdote was just another example of what African American people had to live with in the Twin Cities and Minnesota.

The Early Minnesota Years

Bobby Marshall, standing, second from the left, broke the color line at the University of Minnesota when he played there in 1907. Marshall later played professional football and baseball for several teams. Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Minnesota did not have a Negro League team, but African Americans played on integrated teams as early as 1884 in Stillwater, and on all-black teams, most notably the St. Paul Colored Gophers and the Minneapolis Keystones. During the early twentieth century, several African American athletes stood out.

Bobby Marshall

Bobby Marshall, who competed in baseball, track, and football at the University of Minnesota, played for both the Keystones and the Gophers. Marshall was a key member of the 1909 St. Paul Colored Gophers team that defeated the Chicago Leland Giants for the unofficial championship of Negro baseball.2 A graduate of Minneapolis Central High School, Bobby Marshall broke the University’s color line in baseball in 1907. After graduation, Marshall played football for several professional teams. Despite Marshall’s pioneering, the University’s teams (like the school as a whole) remained overwhelmingly white into the 1960s.

Andrew “Rube” Foster pitched for the Leland Giants in a 1909 game and against the Colored Gophers on several other occasions. According to local historian Fred Buckland, at other times Foster was brought in essentially as a ringer to pitch for the Gophers in key games. One of those games was against Hibbing in 1909, where he pitched a no-hit, 5–0 gem.

Walter Ball

Beginning his career in St. Paul in 1893, Walter Ball played on largely white semiprofessional teams ten years before joining the all-black Chicago Union Giants. In 1907, he organized, managed, and pitched for the St. Paul Colored Gophers, but he returned to Chicago before the end of the season. Ball was still pitching professionally at age 45.

Billy Williams

Billy Williams’s career illustrates some of the dilemmas African American players faced in baseball. Born in St. Paul in 1877, Williams was a standout player on several integrated teams in the region. In 1904, he was the only African American player on the St. Paul Amateur Baseball Association team and the team’s captain. That year the major league Baltimore Orioles asked Williams to join them, suggesting he pass as an American Indian to avoid racist opposition. Williams declined to do this and instead accepted a job with Minnesota Governor John A. Johnson, whom he had met years before on the baseball diamond. Williams went on to serve as the assistant to fourteen Minnesota governors between 1904 and 1957.

Creating Their Own League

The color barrier in baseball grew in the early decades of the twentieth century. In the 1920s, through a gentlemen’s agreement, baseball’s first commissioner, Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis, barred major league teams from playing black teams during the off-season. Landis feared the embarrassment of the white teams losing to “inferior” black players. The agreement also banned black players from playing in the major leagues.

Because of barriers such as these, on February 13 and 14, 1920, leaders of a number of all-black baseball teams met at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri, and established the Negro National League and its governing body, the National Association of Colored Professional Baseball Clubs. Rube Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants, was named president of the association. Initially the league was composed of eight teams: Chicago American Giants, Chicago Giants, Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Kansas City Monarchs, and the St. Louis Giants.

Early Legends

A Winnebago-Dakota Indian, Leland C. “Lee” Davis played catcher for several Negro Leagues baseball teams. At the time this 1927 photo was taken, he was playing for the Kansas City Monarchs. Photo courtesy of the Davis family.

Prior to World War II, Minnesota was home to several semi-pro black teams, including the St. Paul Quicksteps, the Askins, the Bertha Nine, the Minneapolis Keystones, the Minneapolis Colored Giants, the St. Paul Monarchs, and the Marines Red Sox (sponsored by a Minneapolis clothing store). Kansas City Monarch and Chicago American Giant catcher, Leland C. “Lee” Davis, spent several years traveling the Midwest catching for Negro League legend John Donaldson. Lee was a Winnebago- Dakota Indian who played in the Negro Leagues since his skin was too dark for him to play in organized professional baseball. The Negro League pitching star, John W. Donaldson, traveled throughout Minnesota with All Nations teams from 1912 to 1917 and 1920 to 1923. According to historian, Peter W. Gorton, “he deserves examination as a potential Hall of Fame ballplayer, but this gifted left-handed pitcher played in the wrong time period, beginning when there was a lull in the national Black baseball scene corresponding to the time when he was in his prime.”

During a visit to Minnesota in 2003, former Kansas City Monarch and baseball legend, Buck O’Neil reminisced about players he knew and had seen play over the years. Minneapolis standout player, Leroy Hardeman, who was in the crowd that day, looked at Buck and said in his baritone voice, “Maceo Breedlove.”

Buck replied, “Great hitter. Could have played with any of our [Monarchs] teams.” In 1934 and 1935, Maceo Breedlove played for the Twin City Colored Giants against a team that included Robert Leroy “Satchel” Paige, Barney Morris, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, and Hilton Smith. His stats in four games against this team illustrate why he is considered one the greatest sluggers in the Twin Cities segregated baseball history and perhaps baseball history period (AB-17, R-6, H-9, 2B-2, HR-3, batting average .529, and slugging percentage 1.176).

While she was a member of the New Orleans Creoles in the late 1940s, Toni Stone, left, met heavyweight boxing champion Joe Lewis. Photo courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society

Toni Stone

In 1937, sixteen-year-old Toni Stone (Marcenia Lyle Alberga) pitched several games for the Twin Cities Colored Giants. “She was as good as most of the men,” remembered teammate Harry Davis. In the late 1940s, Stone moved to California and played with the San Francisco Sea Lions in the West Coast Negro League. From 1949 to 1952, she played with the New Orleans Creoles of the Negro Southern League. Toni Stone was one of only three women to play in the Negro Leagues, but she was the most prominent. She grew up in St. Paul, and throughout school played baseball on boys’ teams, including an American Legion team. While she lived in St. Paul, Toni was a member of the St. Peter Claver Catholic Church. In 1953, she played fifty games with the Indianapolis Clowns, which one year earlier, boasted a shortstop named Hank Aaron, who went on to have a Hall of Fame career in the major leagues. Toni played her final season in the Negro Leagues with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1954. Like many players before and after her, Toni said that getting a hit off Satchel Paige was her greatest thrill in baseball. On December 19, 1996, the city of St. Paul changed the name of Dunning Park baseball stadium at Marshall Avenue and Dunlap Street to Toni Stone Stadium.

Barnstorming

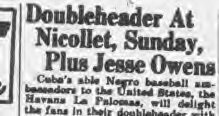

Negro League teams barnstormed throughout Minnesota on a regular basis in the 1930s through the 1950s. They played at Lexington ballpark (home of the St. Paul Saints) and Nicollet ballpark (home of the Minneapolis Millers). As various newspaper headlines attest, they also played other Negro League teams: “Cincinnati Crescents Play Brooklyn Royal Giants at Lexington Park June 24” and “Havana La Palomas versus leading Seattle Steelheads of the West Coast Negro League at Nicollet Park, plus Jessie Owens” or “Harlem Globetrotters play House of David at Lexington Park.”

A headline in the Minneapolis Spokesman newspaper from 1947 captures the essence of one black baseball doubleheader involving two Negro Leagues teams that played at Nicollet Park. Photo courtesy of the Minneapolis Spokesman-Recorder.

Barnstorming was a method for teams to play extra games and make additional money, but even in Minnesota there were challenges for African American athletes. When these visitors came here, they could not stay in local hotels due to segregation, so they usually stayed with black families who lived in the area. The Rexudes, who lived next to what is now Brooks Funeral Home on Rondo Avenue, often hosted black players, including Roy Campanella, when he played for the St. Paul Saints. These players typically ate in restaurants like Dew Drop Inn (later called Booker T’s Barbeque) or Sperling’s, or Goodman’s in St. Paul.

Not everyone had the same expectations of barnstorming teams. Some expected that all-black teams did not come to town to play serious baseball but to entertain through clowning and buffoonery. Some of these African American players recall being chased out of town without payment when they began to beat the hometown team. During the 1930s, a “special attraction” at some games was U.S. Olympic track star Jessie Owens. He appeared many times with barnstorming teams at Lexington and Nicollet ballparks. Owens was featured racing a horse. This was the graduate of Ohio State University and Olympic athlete who had shamed Hitler’s best sprinters in the 1936 Olympic Games when he won four gold medals. In order to make a living following his success in Berlin, however, he was forced to race in this demeaning way against a horse. Writing in 1946, Nell Dodson Russell said in her column in the Minneapolis Spokesman, “The way I see it, maybe he is financially secure, but if he is, I wish he would stop racing horses!”

Barnstorming could be full of hidden surprises. While this is a basketball story, it is also a story of barnstorming by African Americans and the challenges of these ventures. After my junior season of playing varsity basketball at Mechanic Arts High School, my father Louis asked if I wanted to travel with his basketball team for the weekend. These great baseball athletes also barnstormed in basketball. I agreed to go; mainly I was going as the sixth player in case someone needed a rest during one of the games. These guys were former professional, college players and a couple of standout local guys like my father. They had those flashy uniforms like the Harlem Globetrotters.

Reginald “Hoppy” Hopwood briefly played leftfield for the Kansas City Monarchs in the late 1920s. Photo courtesy of the Hopwood family.

The games were in northern Wisconsin; so we traveled most of Saturday in order to arrive for the first evening’s game. The gym was in great need of repair; colder inside the gym than it was outside. The gentleman that showed us around the gym and the locker rooms also shared that the pipes had frozen and we would not be able to shower after the game. We played the game; I was pressed into my substitute role a couple times during the game and had some fun playing. However, it was after that game and our journey to the local eating place that was the surprise of my young life.

We walked into a bar and restaurant, but the other guys stopped to talk with some people that had been at the game. I continued into the bar. I was a hungry teenager! When I walked in, immediately to my left was a long bar with people seated and talking and eating or drinking. I looked to my left behind the bar and there to my surprise was a handmade poster that stated, “Come and see the St. Paul Nigger Clowns play basketball.” It included the date, time, and location. I immediately went outside to the lobby and told my father that we couldn’t eat in there.

He said, “Why?” and followed me into the bar. As I pointed to the poster, my dad and the four other players looked, and they all laughed! I did not see the humor, but I guessed that they had seen it before. WOW, I was shocked that this kind of poster would be allowed in public.

The next day we traveled to our second game, near Lac De Flambeau and a small resort area at the time. Upon arrival, we stopped in front of a small café tucked into a wooded area. As we got out of the car, I looked at the front door of the café and saw the blinds being pulled shut. A hand from behind the blinds turned the sign that said “Open” around to say “Closed.” I continued up the walkway only to find the door locked.

Just then a patrol car pulled up and the officer asked, “Are you guys the basketball team?” My father said “Yes,” and he asked us to follow him. He took us around the lake to another location, which was much nicer, where we could eat. But again, WOW, what a shock!

Based on what Buck O’Neil, “Double Duty” Radcliffe, and other former Negro League players, including local players, have reported concerning the challenges of barnstorming, traveling baseball was not all that glamorous and fun; it had challenges, dangers, and complicated struggles for survival. Their stories and recollections make me think about my father and his safety as he traveled to play the game he loved to play, to make some additional money to help raise his young family, but most of all, to show the talent that he had and maybe gain some sort of recognition with his fellow players from the Twin Cities.

One of his teams, the Twin City Colored Giants, which was managed by George M. White, traveled all over the five-state area and to Port Williams and Port Arthur, Canada. All these years later, I cannot even imagine playing the game you love, while fearing what the journey to the next ballpark might hold in store for you and your teammates. I’m so glad for my mother that my father always returned home, safe and sound, or at least that we knew, safe!

The End of the Color Barrier

While many Negro League players held on to the dream to play in the major leagues one day, a few were to be considered, such as Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella, Jackie Robinson, and others. In 1945 Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, signed Jackie Robinson of the Kansas City Monarchs. At the time, Rickey was the only baseball executive who wanted to integrate the league. Jackie was sent to play for the Montreal Royals, a Dodgers farm team, for the 1946 season. In 1947 Robinson went to Cuba for spring training with the Dodgers. Here a talented, white, St. Paul athlete named Howie Schultz became Robinson’s mentor as he showed him how to play first base. Then on April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson trotted out to first base and replaced Howie Schultz. That event broke the color barrier in the major leagues. About a month later, the Dodgers sold Schultz’s contract to the Phillies for $50,000.

Howie Schultz, second from the left, a St. Paul native, tutored Jackie Robinson, fourth from the left, on the fine points of playing first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League during spring training before Robinson broke the color line in the Major Leagues on April 15, 1947. Photo courtesy of the Schultz family.

Skip Schultz, Howie’s son, told me the following story, which his father had shared with him. Later that season on the Dodgers first trip to Philadelphia, the Phillies pitcher hit Jackie with his first pitch when he came up to bat and knocked him down. As Jackie picked himself up and trotted to first base, the crowd and Phillies dugout yelled racial slurs. When Jackie arrived at first base, Howie said, “Jackie, how do you take this day after day?” Jackie responded, “It’s okay, Howie. I’ll have my day.” This story is very special to me because Howie Schultz was later an influence on my high school athletic career in basketball and baseball as my coach.

In 1947 the Cleveland Indians signed twenty-two-year-old Larry Doby of the Negro Leagues Newark Eagles. According to Bob Kendrick, former Negro Leagues Baseball Museum marketing director, that “while [the signing of Robinson, Doby, and other Negro Leagues stars] was a tremendous occasion, it was the beginning of the end for what was known as Negro Leagues Baseball. It was devastating to black-owned businesses that supported Negro Leagues baseball; hotels, restaurants, and other service businesses.”

On August 26, 1947, Dan Bankhead became the first black pitcher in the Major Leagues when he took the mound in the second inning against the Pittsburgh Pirates. A year later he returned to the St. Paul Saints to join Roy Campanella as the first black players on that local team. In 1948 Ray Dandridge and Dave Barnhill became the first black players to play for the Minneapolis Millers at Nicollet Park. Professional baseball had become integrated, but major league teams then began to employ a quota system to keep the number of black players to a handful.

This news photo from June 4, 1946 captures the excitement and excellence of high school baseball competition in St. Paul. Photo courtesy of the St. Paul Dispatch.

The Local Players

Local players may be defined a number of ways; some were born here, some moved here to work, and some barnstormed through and stayed. Some of these players had long careers and played for many teams. Two prominent coaches, Dennis Ware and George M. White, led practices and games at The Hollow Field (St. Anthony Avenue and Kent Street) and Welcome Hall Field (St. Anthony Avenue and Western Street). The tremendous rivalry between all-black Minneapolis and St. Paul teams was witnessed at Sumner Field (Minneapolis) and Welcome Hall Field (St. Paul). This rivalry actually continues today in high school basketball and football.

According to Norm “Speed” Rawlings, who worked across the street from the field at Garrett’s Pool Hall, “People lined up all around Welcome Hall Field” when there was a game between these all-black clubs.

Some of the players of the 1940s and 50s include: Charlie Anderson, Larry “Bubba” Brown, Horace Brown, Pete Buford, Ken Christian, Leon Combs, Jack Cooper, Albert Cotton, John Cotton, Buda Crowe, Hiram “Ham” Douglas, Jake “Rocking Chair” Foots, Lloyd Gamble, Leroy Hardeman, Lloyd “DuLov” Hogan, Norman “Rock Bottom” Howell, Johnny Kelly, Jimmy Lee, Clarence Lewis, Jake Lynch, Sam Lynch, Vic McGowan, W.D. Massey, Paul Michaels, Leon Presley, Red Presley, Drexel Pugh, Cleveland Ray, Paul Ray, Dwight Reed, Stanley Tabor, Martin Weddington, Lloyd Wendel, Louis “Pud” White Jr., Sid Williams, and Chink Worley.

Local sports pioneers Larry “Bubba” Brown, Ken Christian, John Cotton, James Millsap, and Jim Robinson remember the players this way:

O’Dell Livingston, left, played in the outfield in the Negro Leagues when he was a member of the Kansas City Monarchs, the New York Black Yankees, and the Pittsburgh Crawfords in the late 1920s and early ’30s. The date of this photo is unknown, as is the name of the player on the right. Livingston later played for the Minneapolis House of David team in the 1940s. Photo courtesy of the Livingston family.

Chink Worley was an outfielder with a great arm. When the ball was hit to Chink with runners on base, it would not be unusual as he waited for the ball in the air, to yell, “Tag ’em” as he was always confident of throwing the runner out.

Vic McGowan, a right-hand hitter, was a great swing bunt hitter and played with the New York Cubans.

Jake “Rocking Chair” Foots, a catcher, could catch and throw to second base while sitting in a rocking chair. He played with the Indianapolis Clowns.

Ken Christian, a left-handed hitter, played all positions. He had an amazing drag bunt technique. He’d hold the bat with his left hand, and start running toward first while he was still in the batter’s box and making contact with the pitch. By the time an infielder picked up the bunted ball, Christian would be safely past first base. He tried out for the Kansas City Monarchs.

Babe Price, considered one of the best pitchers of his time, would show up for a game— late. Then someone would always yell out loud, “Here comes the Babe!” His was always the great entrance.

Cecil Littles, a third baseman, began playing for the Bartlesville Blues, and in early 1951, played in the Western Canadian League with the Estevan Maple Leafs. Cecil had tremendous reflexes; it was hard to hit the ball past him. On several occasions he was seen dropping to his knees to catch a hit ball and while still on his knees throw the runner out at first base.

John Cotton, who graduated from Marshall Senior High School in 1943. According to John, he “started playing with Coach Ware when [he] was only fourteen years old. I remember learning the game from the older players, the swing bunt or a delayed steal. These things helped me when I played in high school.” Cotton was All City nine times; first team in baseball for three years in a row, second team his sophomore year in football and then first team in his junior and senior years. He was also second team his sophomore year in basketball and then first team the next two years. He was an outstanding athlete. John Cotton should have been named one of the top 100 St. Paul City Conference male student- athletes at the Centennial Banquet in 1999, which celebrated the first century of the St. Paul City Conference.

Louis “Pud” White Jr., who was honored as one of the top 100 male studentathletes at the Centennial Banquet in 1999, was All City in three sports (baseball, basketball, and football). To complete his high school career in 1946, he won the St. Paul City Conference baseball batting title with a torrid .600 batting average, considered to this day the conference record. Louis is highlighted in the exhibit in an interview with former acquaintance Buck O’Neil, who tried to recruit White out of high school to play for the Kansas City Monarchs. The interview was held in front of the Satchel Paige statue in the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, Kansas City.

According to Jim Robinson, a long-time observer of baseball in the local area, some of these players were as good as Howie Schultz, the white, St. Paul star athlete who played professionally for the Brooklyn Dodgers, Philadelphia Phillies, and the Minneapolis Lakers basketball team.

Additional information about the players who “passed here along the way” to the Major Leagues and their statistics while playing in Minnesota

The Minneapolis Millers, American Association, Triple A

Affiliated with New York Giants (1946–1957); Boston Red Sox (1958–1960)

Played at Nicollet Park (1896–1955) at the corner of Nicollet Avenue and Lake Street, Minneapolis and at Metropolitan Stadium (1956–1960) in Bloomington, Minn.

1949 Ray Dandridge .362 BA; .487 SLG%; NLP; HOF (First African American player for the Millers), 1950 American Association MVP, .311 BA; .405 SLG %

1949 Dave Barnhill, pitcher (1949–50–51) NLP

1951 Willie Mays* .477 BA; .799 SLG% NLP HOF (Only here 34 games before being called up to the New York Giants)

1951 Henry “Hank” Thompson* .340 BA; .774 SLG%; NLP

1951 Artie Wilson .390 BA; NLP

1955 Monte Irvin* .352 BA; .612 SLG%; NLP

1955–56 Willie Kirkland .293 BA; .589 SLG%; 37 HRs

1956 Ozzie Virgil .265 BA; 10 HRs

1956 Bill White (After his baseball career in the Major Leagues, White went on to become a baseball executive and later president of the National League)

1957 Orlando Cepeda .309 BA; .508 SLG%; 25 HRs; HOF

1957 Felipe Alou

1958–59 Elijah “Pumpsie” Green .320 BA; .442 SLG%

St. Cloud Rox, Northern League, Class C

Affiliated with New York Giants (1946–1957); San Francisco Giants (1958–1959); Chicago Cubs (1960–1964); Minnesota Twins (1965–1971)

Cepeda

Brock

1953 Ozzie Virgil, infielder .259 BA; 7 HRs

1954 Willie Kirkland, outfielder .360 BA; .640 SLG%; 27 HRs

1955 Tony Taylor, infield .267 BA

1955 Leon “Big Daddy Wags” Wagner, outfielder .313 BA; .573 SLG%; 29 HRs

1956 Orlando Cepeda, infielder .355 BA; .613 SLG%; 26 HRs; 112 RBIs; HOF (Northern League Triple Crown Champion)

1958 Matty Alou, outfielder .321 BA; .400 SLG%

1961 Lou Brock, outfielder .361 BA; .535 SLG%; 14 HRs; HOF

1968 Alexander Rowell, outfielder .301 BA

St. Paul Saints, American Association, Triple A

Affiliated with Chicago White Sox (1936–1942); Brooklyn Dodgers (1944–1957); Los Angeles Dodgers (1958–1960)

1948 Dan Bankhead, pitcher NLP (First African American pitcher in the Major Leagues for Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947)

1948 Roy Campanella, catcher NLP .325 BA, .715 SLG%, 13 HRs (First African American to play in the American Association and for the St. Paul Saints)

1949–51 Jim Pendelton (in 1950) .299 BA; 98 RBIs; 10 HRs

1952 Edmundo “Sandy” Amoros .377 BA; .544 SLG%; 19 HRs

1954 Charlie Neal, infielder NLP; .272 BA; .451 SLG%; 18 HRs

1956 Solomon Drake, outfielder .333 BA; .600 SLG%; 13 HRs

1956–60 Lacey Curry, outfielder and second base .306 BA

1959 Earl Robinson .261 BA

Abbreviations:

BA–batting average

SLG%–slugging percentage

NLP–Negro Leagues player

HOF–Major League Baseball Hall of Fall member MVP–Most Valuable Player

HRs–home runs

*In the 1951 World Series after Don Mueller was injured, Hank Thompson of the New York Giants was forced to play right field, thereby teaming with Willie Mays and Monte Irvin to make the first all-black outfield in Major League history. Photos courtesy of the Stearns County History Museum and Research Center, St. Cloud, Minn. Cepeda Brock

John Cotton was a star baseball player in the 1940s and ’50s in St. Paul. Photo courtesy of the Cotton family.

The ’50s and ’60s

While Negro Leagues Baseball teams still barnstormed through Minnesota, including Minneapolis and St. Paul, baseball remained “the game” in the Rondo neighborhood.

It was organized and played at Ober Boys Club (formerly Welcome Hall Field) and at Oxford Playground (at the corner of Oxford Street and Rondo Avenue). Many tremendous athletes played baseball until they attended high school, where they would switch to track or football, sports in which there was a potential for earning a college scholarship. Thus while baseball in that era may have been integrated, opportunities after high school were still limited.

Some of the names of those baseball players from the mid-1950s include Mike Buford, Ronnie Harris, Sonny McNeal, Bill Peterson, Tony Vann, and Steve Williams. Players from the late 1950s and ’60s include Bernie Buford, Larry Buford, Kenny Christian Jr., Tom Hardy, Roger Neal, Mickey Oliver, Buddy Parker, Leroy Parker, Wells Price, Ray Whitmore, Steve and David Winfield, and Frank White.

The 1950s and ‘60s also brought another change to Minnesota—the popularity of fast-pitch softball. Of course a number of all-black teams made the change from baseball to fast-pitch softball. The Ted Bies Liquors club from St. Paul was one of those teams. By the late sixties, however, another change was occurring all around the Twin Cities: baseball was on the decline.

Once the Winfield brothers, Steve and Dave, had graduated from high school and moved gone on to the University of Minnesota, a gradual shift of interest from baseball to basketball accelerated and became a large boom.

In 1968 the Attucks Brooks American Legion baseball team from St. Paul won the Legion’s state championship. What made this team so notable was that after so many years when baseball played by African American youths had flourished in the city, the champions’ roster included only three black players, Steve Scroggins, front row left; Steve Winfield, standing fifth from the left; and David Winfield, standing sixth from the left. Bill Peterson, standing, far right, was the team’s coach. Photo courtesy of Bill Peterson.

What It All Means to Me

In putting this exhibit together at Landmark Center and doing the research for it and this article, what continues to amaze me is that this untold story of Minnesota black baseball is only beginning to be shared. I have learned so much. I took on this project without knowing how important it would be to our history, to the history of African Americans and to people of all races in the local community.

I appreciate those individuals who pushed and challenged me to do more. Without them, this story and the exhibit would never have come together. I have received many phone calls from people who have pictures, newspaper articles, or stories of their parents or grandparents that they want to share with me so that my account is more complete and inclusive.

The Ted Bies Liquor Fast-Pitch Softball team about 1955. Ted Bies, who sponsored the team, is standing on the far right. Photo courtesy of Frank White.

The number of people who have approached with me since the exhibit opened and shared their appreciation of this way of telling the story of those who “played for the love of the game” has been overwhelming. They are excited for their children to be learning this important piece of history because they want these young people to have a more complete understanding of local history—the real picture—not some made-over story.

For the African American and Rondo community, we are appreciative of finally getting some recognition for the many husbands, fathers, grandfathers, and friends who played baseball in the middle of the twentieth century. This recognition was previously slipped under the rug and denied only because of the color of their skin; not because they could not play the great game of baseball. As one newspaper reporter shared with me, “You’re bringing these guys back to life.” I never looked at it like that. I just wanted to let people know that these guys could play the game and were very good ballplayers.

Frank M. White attended the University of Minnesota. He is the manager of Recreation Programs and Athletics for the city of Richfield, Minn. He is also a long-time basketball official and is currently the Minnesota Twins RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities) coordinator.

Endnotes

1. I am indebted to Mollie Spillman, Will Peterson, and the Ramsey County Historical Society for their help. This project could not have been completed without them. In addition the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City has provided excellent support to me for this exhibit. I also thank my family and friends for their support and assistance, with listening to me talk about this idea. Especially I thank my fiancée, Lisa, and my daughter, Janae, for continuing to support and be there for me during the busy times of completing the work for this important piece of local history.

2. For an excellent biographical profile of Robert W. (Bobby) Marshall, see Steven R. Hoffbeck, “Bobby Marshall: Pioneering African American Athlete,” Minnesota History 59, no. 4 (Winter 2004): 158–74.

3. Two excellent resources for the history of the Negro Leagues are Robert Peterson, Only the Ball Was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1970; with a new preface, New York: Oxford University Press, 1992) and James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994).

4. Peter W. Gorton, “John Wesley Donaldson, a Great Mound Artist,” in Steven R. Hoffbeck, ed., Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 107.

5. For more information on black baseball in Minnesota, see Hoffbeck's Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota.

On May 5, 2006, the Minnesota Twins honored local African American baseball legends of the past and local youths who had participated in the Twins-sponsored RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities) program. Seen here, standing left to right, are Twins coach Jerry White; local legends John Cotton and Cecil Littles; Rondell White, a Twins player; legend Ken Christian; Shannon Stewart, a Twins player; legend Leroy Hardeman; and Torii Hunter, a Twins player. Photo courtesy of Frank White.